UCLA/Mellon Foundation Interns Make Southern California History

Internship at the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC)

by Riona Tsai || June 2025

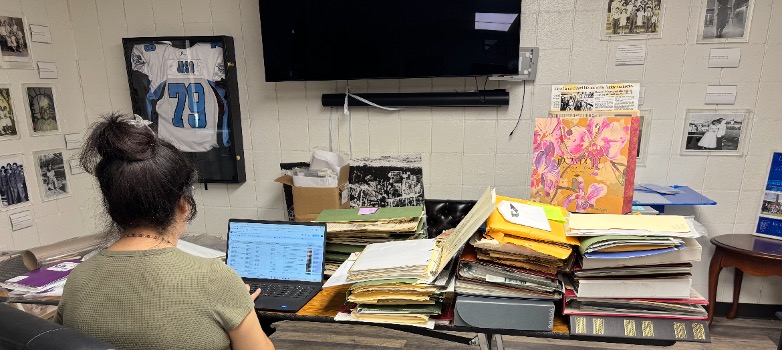

In 2021, I began working as an intern at the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC). At this time, I was an undergraduate student at UC Riverside. I began my internship doing research on City Market Chinatown as a part of the Five Chinatowns Project for my history major and worked on various other projects as a research intern. Now as an archival intern at CHSSC, I get to work hands-on with processing their physical and digital archival collections.

As an archival intern, I’ve worked on many different types of projects, but I have been focusing on processing collections to ensure accessibility to these archival collections for users during my time here. In my first few months, I mostly worked on helping the community archivist at CHSSC process physical collections since I had never fully processed a collection by myself before. Once I got more comfortable with the process, I began processing collections by myself. I have fully processed a few collections, starting from arrangement, description, and creating and uploading finding aids into Online Archive of California (OAC).

At the same time, I have been working on implementing the Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS) into CHSSC’s digital oral history collections. OHMS is a software created by the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries that enhances accessibility to oral history interviews through word-search level capability, time-correlated transcripts, interview indexes, and much more. Starting with CHSSC’s Duty and Honor Collection, I have been figuring out how to use OHMS and creating a workflow for future use with the rest of their oral history collections.

I have had the opportunity to work with many types of archival materials at CHSSC. There are even some materials that CHSSC doesn’t have policies for processing yet, thus, the archives team and I have to do research and figure out how to establish the archives’ procedures with certain types of materials. An example would be in the first collection I fully processed myself, Chinese American Restaurants in Los Angeles Menu Collection, which contained a few matchbooks from LA Chinatown restaurants with live matches in it. We had some trouble with that since none of us on the archives team had any experience archiving matchbooks at all. We eventually had to buy a specific type of box to keep them in, but it took us a while to figure that out.

Overall, I’ve been able to work on an amazing variety of archival projects here. My experiences at CHSSC have been incredibly valuable to me, and I am incredibly proud to be a part of preserving these histories.

Archiving in Motion: Community, Collaboration, and Storytelling at LAAPFF

by Blair Black || May 2025

Volunteering at the L.A. Asian Pacific Film Festival (LAAPFF), presented by Visual Communications (VC), was a deeply moving experience that reminded me of how essential collaboration is to sustaining community memory. As an archivist, I often think about legacy in terms of preservation—but working the festival taught me that legacy is also carried in relationships, shared labor, and intergenerational storytelling. At LAAPFF, all of those elements came together in real time.

One of the most powerful moments was the L.A. premiere of Third Act (2025), a documentary by Tadashi Nakamura about his father, Robert “Bob” Nakamura—”Father of Asian American cinema,” educator, and co-founder of VC. The screening took place at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), where Tad works as the Frank H. Watase Media Arts Center Director, adding another layer of meaning. The space was filled with generations of community members: former students, artists, activists, and collaborators. Family and friends gathered alongside members of the Little Tokyo community to celebrate a life and legacy that had shaped so much of Asian American media history.

Photo Courtesy of Visual Communications

What made the film even more meaningful was the way it seamlessly wove in archival footage and photographs from VC’s collection—some of which Tad had personally worked with over the years. These archival materials didn’t just provide visual context; they were part of the story. They bore witness to Bob’s journey and the evolution of the Asian American movement itself. Seeing these materials repurposed in a living, breathing work of art affirmed for me how archives are not static—they’re active participants in storytelling.

As an archivist, moments like this affirm the importance of our work—not just in preserving the past, but in making it accessible for future creativity and reflection. VC’s archives have long been a resource for filmmakers, scholars, and community members. What Third Act demonstrated so beautifully is that archives, when rooted in community, can serve as bridges between generations—holding histories that are as personal as they are political.

Photo Courtesy of Visual Communications

That spirit of shared purpose extended far beyond the screening. Every shift I worked at the festival—from check-in to ushering to supporting panels—was powered by a collaborative rhythm. VC staff led with care and humility, creating space for volunteers, filmmakers, and community members to contribute meaningfully. There was a palpable sense of joy in working together—whether we were troubleshooting tech or sharing snacks in the green room.

What sets LAAPFF apart is that it’s not just an event—it’s an embodiment of VC’s values: cultural self-determination, intergenerational exchange, and community-based storytelling. And archives are deeply entangled with the community they represent. Whether materials are being pulled for a documentary or shared at a tagging session with elders, they’re part of a larger ecosystem of memory and movement.

To uplift community, we must work collectively. That means building trust, honoring legacy, and making space for new voices to emerge. At LAAPFF, I saw all of that in action—and was reminded that archival work doesn’t end with preservation. It begins again each time someone tells a story.

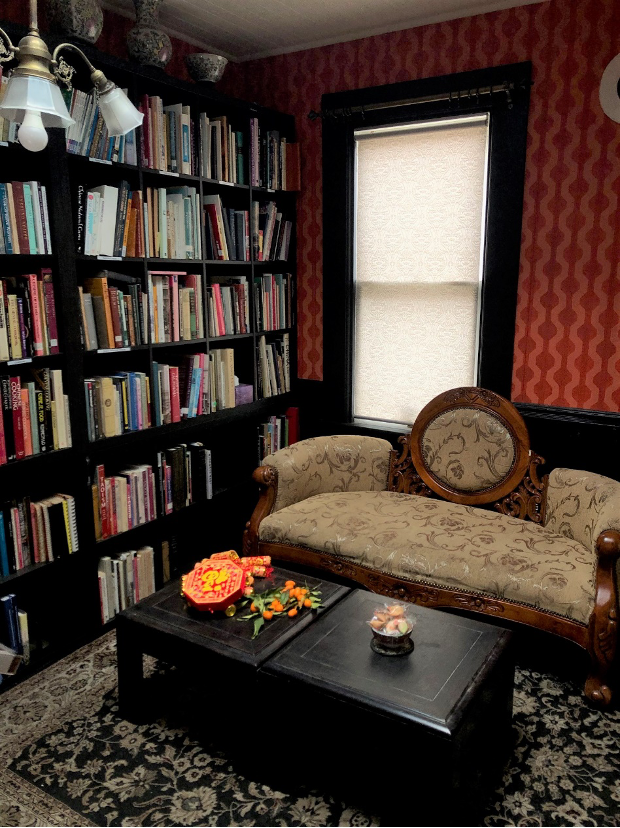

Sharing Lesbian Joy at the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives

by Sam Stroud || April 2025

During my time as an intern at the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, I’ve gained experience in many aspects of the archival process. I’ve processed collections, written finding aids, digitized materials, and created metadata for digital collections– to name just a few of my intern tasks. The skills I’ve gained through this position have set me up for success, especially as my time as a student is coming to a close and I am on the hunt for full-time employment. However, perhaps the most meaningful thing I’ve gained from this experience is the joy of connection to my community, its history, and its elders.

Every day that I go to work at the Mazer is a good day. By now, the staff at the Mazer are used to my giddy excitement, awe, and immense gratitude for the collections. Getting to exist and work in a space where I am surrounded by lesbian stories and history has been so wonderful and overwhelming in the best way. For me, the only thing better than going to work at the Mazer is inviting others to enjoy the space alongside me.

On January 26, 2025, I hosted a volunteer day at the Mazer for UCLA MLIS students to visit the archives, help us move collections, and catalog books. Not only did we get far more done than we had originally set out to, it was also a day full of joy, community, and newfound friendships. Of the 15 volunteers who came to the event, many of them have remained connected to the archives in the months since as regular volunteers.

MLIS students at the Mazer’s volunteer day

The success of our volunteer day set the tone for the events the Mazer has planned for the rest of the year. In early March, the Mazer held an Open House, which was attended by dozens of lesbians, queer and trans folks, and allies from across generations. In preparation for the event, I designed branded pin-back buttons featuring photos of iconic lesbians from the Mazer’s collections. As I made buttons throughout the event, lesbian elders approached me to take a button and tell me stories of their friends who were pictured on the buttons. Not only were the buttons great conversation starters, but my button-making station also raised over $200 in donations during the two hour event.

The Mazer’s 1.5 inch button maker and branded pin-back buttons

The success and joy of Mazer events is set to continue throughout the spring and summer. We’re launching a lesbian comic book club and plan to host regular movie nights in the coming months. While there are only ten weeks left of my Mellon-funded internship at the Mazer, I know my involvement and connection to the archives is one that I will maintain and cherish for the rest of my life.

La Historia: The History of a Community Within the Files of an Archive

by Priscilla Avitia || March 2025

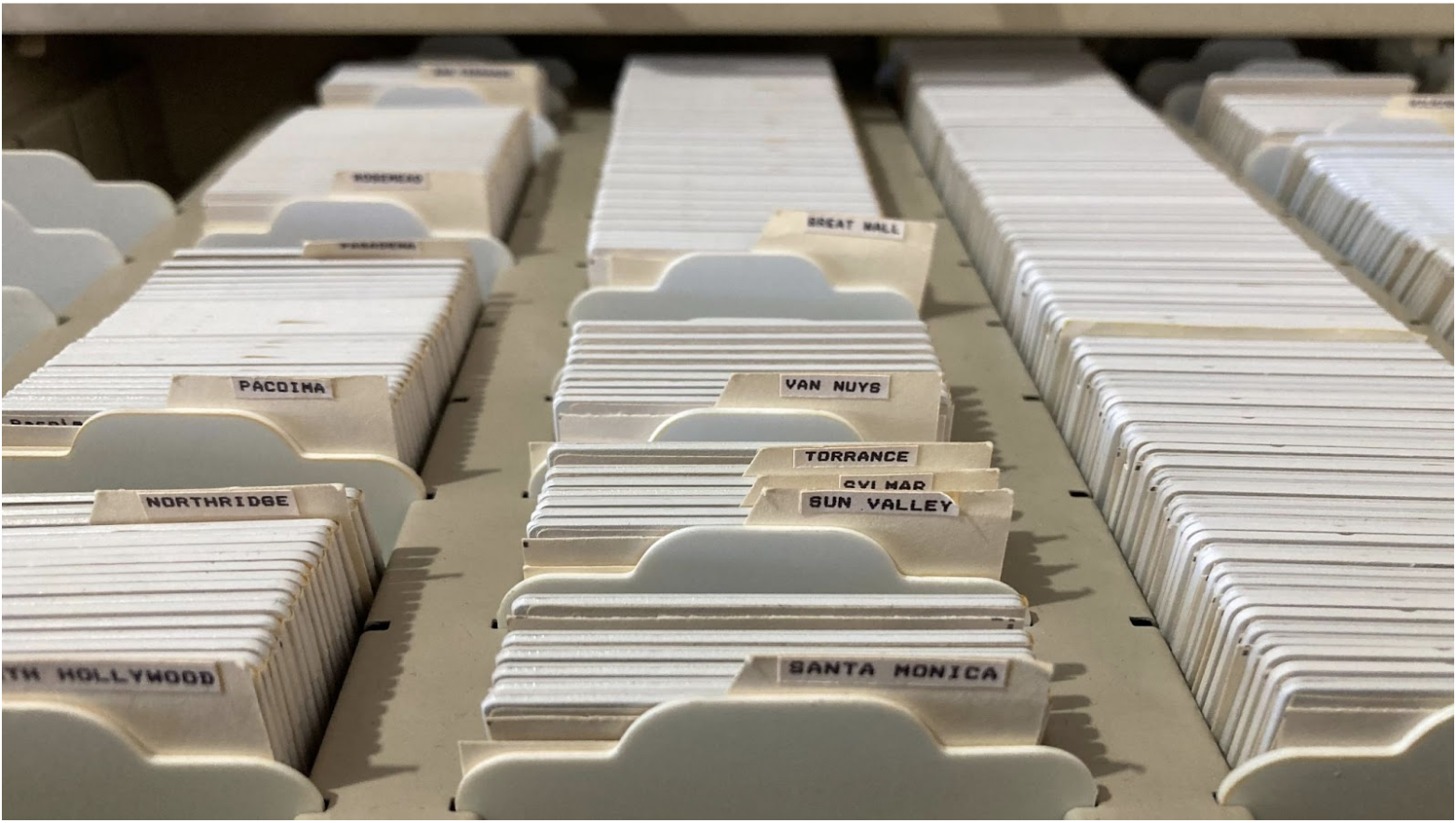

I first visited La Historia Historical Society Museum during their Mellon Grant showcase. Rosa Pena, La Historia director, Bianca J. Sosa-Phal, La Historia archivist, and Krystal Mendez, a former UCLA Mellon intern, each gave short presentations. They discussed the projects they’ve worked on and events they’ve hosted, in addition to their future goals for the museum and archive. After the presentations concluded, I had the opportunity to walk around the museum and observe the photographs of military soldiers, school children, family gatherings, and other objects of daily life. It was the first time I’d seen the history of Mexican Americans as a museum’s sole focus.

La Historia began as a gathering place for family, friends, and neighbors to share their stories and photos. The museum became official to ensure their El Monte and South El Monte history was told and controlled by the community. The museum, and later archive, saw large amounts of donations over the years. People were excited to see their families on the walls of La Historia. These donations also brought back memories for many elders who came to visit.

In my time at La Historia, I’ve worked on establishing a collection management system (CMS) to track donations and loans. Originally, I’d planned to use a well-known CMS but due to resource limitations, I pivoted to expanding the pre-existing spreadsheet in a new format that allowed me to link various pages. I focused on physical donations and loans in the archive and museum to give users the ability to find materials faster and more efficiently. As well as experiencing a better overall understanding of our collections and items.

Bianca and I spent several days together conducting inventories with varying levels of thoroughness. First, we reviewed and took note of what objects and materials we had and what condition they were in. The final checks focused on existing and missing documentation, noting rehousing material needed, and future possible projects for future interns and volunteers. I spent most of my time getting to know the materials by looking at each photo one by one, reading letters written by El Monte and South El Monte students from past years, feeling the clothes, flipping through scrapbook pages, such as one crafted by a mother who wanted to document her daughter’s school days, reading “Hicks Camp: The Beginning of the End” written by a principle in 1956, and more. This experience allowed me to form connections with people whom I have never met. The project I’m working on goes beyond simply assigning numbers to collections and items; it allows those who enter La Historia the opportunity to form those same connections.

As I write this, my time with La Historia is far from over. I have much that I want to accomplish and learn. I am grateful to the community of El Monte and South El Monte for allowing a South Bay kid to listen to their stories and work with their artifacts. As a Mexican American, I am in awe of the hard work and dedication that La Historia has put into ensuring that our community is correctly represented and protected.

Festival for All Artists: Moments from the Skid Row History Museum and Archive

by Ana Elizabeth Lara Beltrand || February 2025

My experience at the Skid Row History Museum and Archive is something I haven’t stopped talking about. On my first day, my supervisor Henry and I did a data walk, taking in the contemporary landscape of Skid Row. This was an excellent first introduction to the philosophy and strategies of the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD), apart from its fantastic website. LAPD is the force behind the Skid Row History Museum and Archive, which continues to advocate for the agency and presence of people at Skid Row. Our data walk discussed how each street in Skid Row has a history. That is histories of zoning laws, surveillance, discrimination, tension, and current gentrification. During my tasks, I sometimes encountered numerous pictures in the archive from before the local firehouse was ordered to take “Skid Row” off its ambulances and rigs.

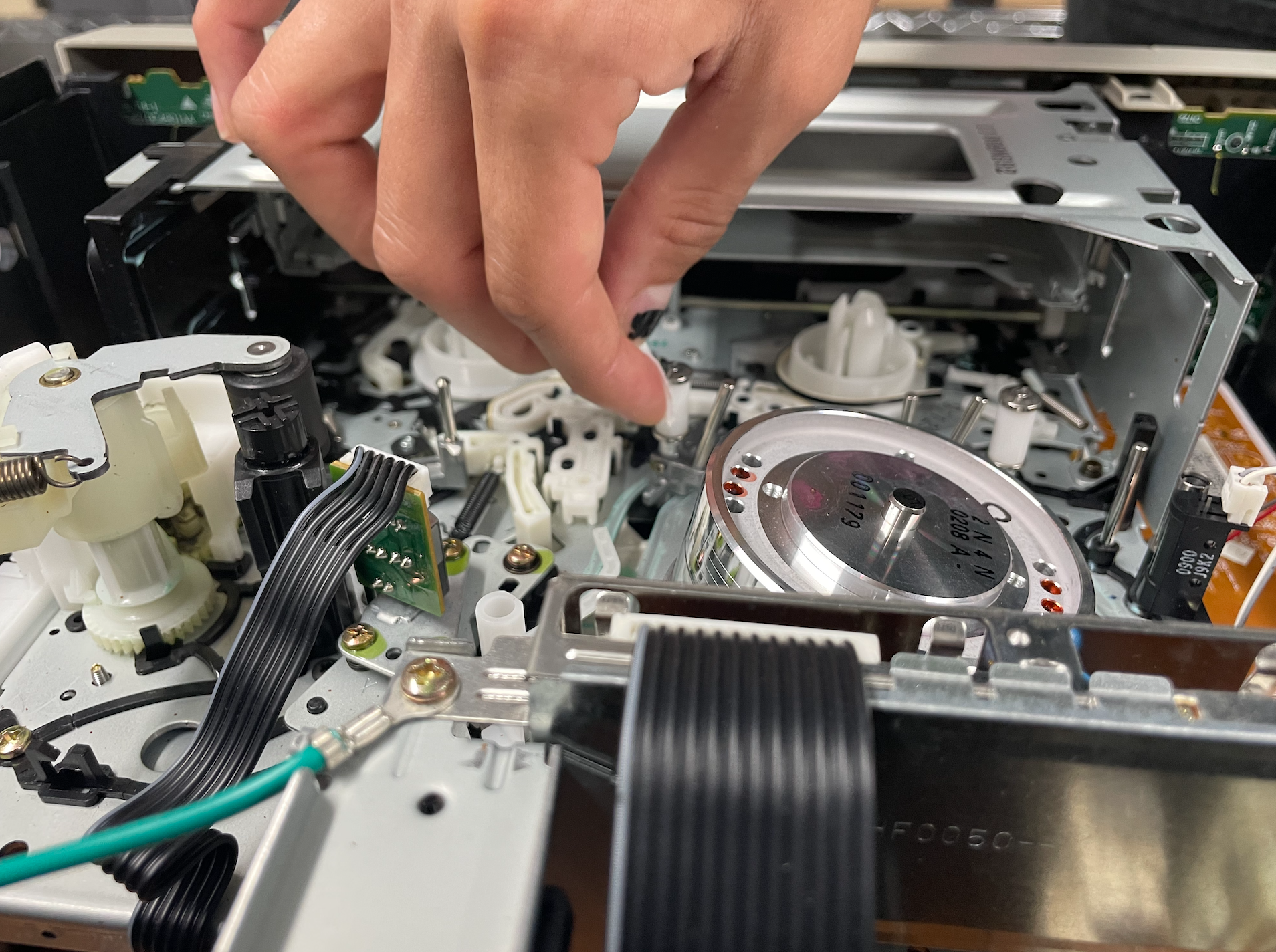

The Skid Row History Museum and Archive approaches its work with immense respect and humanity, ensuring the community is represented authentically. In my role, I’ve worked on inventory projects, applying classification and cataloging methods that I’m familiar with but now with liberties of advocacy. My mentors, Henry and Zach, have been incredibly generous in sharing their knowledge and inviting me to contribute my ideas to their systems and philosophies. I’m deeply grateful for the skills I’ve gained in Excel and PastPerfect in a setting that aligns closely with my passion for community-centered work. With another intern, Franny, I been practicing large digitization and editing projects on DV and VHS media formats. It’s a privilege to see my Los Angeles community through this lens and to witness the performances, theater, and projects of the LAPD and Skid Row locals.

Six months later, as I organize the archive every other week, I recognize faces, places, and perhaps even the intention of the moments captured. Whether it’s a group photo or an image of an empty lot, considerable effort is dedicated to ensuring that the archive reflects the true dignity of this community. I have felt deeply entrusted to assist in the archive and engage with people at various community and archive events. Despite constant negligence, misrepresentation, erasure, and ostracization, the Skid Row community is one of storytellers, advocates, and organizers of hope. Art is vital in mediating difficult and painful conversations at the Skid Row History Museum and Archive. Through this, I have witnessed countless moments of spontaneous kindness, with people sharing supplies, striking up conversations, and ensuring no one is truly alone. I frequently reflect on what I hope someone unfamiliar with Skid Row will grasp when they come across this inventory. The most striking aspect is the joy seen in the events, the acts of resistance, and the individuals.

I had the honor to volunteer at the Festival for All Artists, which, as it states, celebrates all artists of Skid Row. I spent an incredible weekend facilitating simple art activities at General Jeff Memorial Park. The main stage had all types of excellent performances. The enthusiasm of Skid Row residents, from children to adults, is contagious. I was excited alongside some children as we created simple instruments from cardboard or shared stories about our day. The festival is hosted for other organizations that bring art, food, materials, resources, or compassion to the community. I had the chance to chat with an outreach librarian from the Los Angeles Central Library. Together, we handed out handheld visual aids for reading and invited people to the library, reassuring them that they were always most welcome. I want to be a librarian or archivist who can communicate to people that they don’t need to apologize for existing, and that’s what makes my internship site so extraordinary: A place where, despite what the world tells you, you belong. Your presence is part of continuing histories.

I want to close my recap by describing a moment from the festival: someone began singing “Let It Shine” on the stage. One voice after another, friends inviting other friends. People learn the lyrics on the spot, while others add their twist. What started with a handful of people on the park stage grew into a larger group sprawled over the park entrance, singing and dancing together, creating an impromptu melody that lasted about ten minutes. Ten minutes that I can revisit in the archive one day. I remember feeling a euphoric sense of hope while immersed in singing and the community. This moment made me believe things could and will get better. I have felt the embodiment of archival optimism throughout these past six months. Community archives have the power to radiate symbolic joy.

Community LAMs: Preserving the Messy Ties that Bind at CHSSC

by Michaela Telfer || March 2024

Constructed in the 1930s, Los Angeles’ Union Station now sits on the former location of the city’s original Chinatown. By destroying Chinatown and the surrounding area, the Union Station project forcibly displaced both Chinese American and Mexican American residents who, in response, established new neighbourhoods like “New” Chinatown. Despite the destruction of Old Chinatown, however, its history and the lives of its residents persist in the papers, archaeological objects, photographs, and stories now held by the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC). While no collection could ever tell the entire story of a community, the diversity of objects held at CHSSC do go a long way towards preserving the often-untold stories of the many individuals, families, and organizations that have kept Los Angeles’ Chinatown alive through activism, education, labour, celebrations, and the daily acts of living. Since October, I have contributed to making these histories accessible at CHSSC through various projects and, through these projects, have experienced the benefits of community archiving practices for preserving the complex, messy ties that hold a community together.

CHSSC was founded on November 1, 1975, and is housed in two 19th-century Queen Anne style houses and a converted garage on Bernard Street in the heart of Chinatown. The main goals of the organization are to preserve and share the history of the Chinese and Chinese American community in Southern California. To achieve these goals, CHSSC maintains a library, archives, and exhibit space as well as conducting tours of Chinatown and other programming. Working in this kind of flexible space requires a diverse set of skills, especially when it is all conducted by a small team. Since starting at CHSSC, I have taken on many different kinds of projects like processing collections with the help of ArchivesSpace, including undertaking basic preservation practices on paper materials and digitizing fragile materials, grant-writing, and cataloguing digital photographs. The breadth of skills that I have learned just by addressing daily archival needs at CHSSC speaks to the many modalities necessary to properly preserve community histories.

Amid recent conversations on whether and how to increase cooperation between Libraries, Archives, and Museums (LAMs), the different sections of CHSSC are already operating as a kind of blended LAMs space which serves as a major advantage to their stewardship over collections. CHSSC doesn’t just hold archaeological materials from Old Chinatown, for example, but also the institutional paperwork that tracks those materials and books and exhibits that cite those materials and explain their history and significance. Often, when I have a question about a document I’ve found while processing a collection, I’ll (sometimes unexpectedly) find the answer to that question in a book, photographs, or exhibit materials already held by CHSSC or even by recognizing a building that I often walk past on my lunch breaks. This blended space, which extends physically outside of the organization itself and into the neighbourhood, allows for a fluid, exploratory experience of the collection for both the user and the archivist by linking together important historical figures and events in unexpected ways. The interconnections between the three major spheres of the collection (LAM) speak directly to the purpose of the organization because they reflect the complex, fluid connections linking together communities; communities are not solely structured by ordered paperwork but by relationships, chance encounters, and individual choices that aren’t always obvious when only viewed from one perspective.

At CHSSC, I have been very lucky to preserve these connections in a collaborative space where I can directly contribute to archival decisions. I am very grateful to Andy Tan, Chelsea Liu, Linda Bentz, Albert Lowe, and the other board members, staff, and volunteers who have given me the opportunity to care for CHSSC’s collections.

La Historia Society and Museum Continues to Preserve and Actively Engage with Community

by Krystal Mendez || February 2024

The first time I stepped into La Historia, I remember a patron coming in to look for a picture of their dad. While there was no photo to be found, the patron found an old high school yearbook by roaming around the museum. They excitedly grabbed it and flipped to the page with a picture of their dad. A whisper in my head said, “To suddenly discover yourself existing.” There is a lot of power in community archives. For some people, it might be walking into a space like La Historia and thinking, “I can’t believe someone cared enough to preserve this – to preserve what is related to me…about me.”

As a Community Archives Lab/Mellon Intern, I am entrusted to care for information and materials that come from the El Monte and South El Monte area. Over time, I have become familiar with the stories that come through the archive as I start to recognize faces and names, see people grow, and read and hear about both heartbreaking and heartwarming stories. As archivists, we are given glimpses into the lives of peoples and the past of spaces.

Bianca Sosa-Phal (Archivist of La Historia) and Rosa Peña (President of La Historia) have trusted me to pursue my passions as an intern. I’m highly invested in the field of preservation, so they have allowed me to hone in on my skills, lend them my knowledge and learn more about preservation as I work on collections. So, I find myself working in a variety of tasks between mending and rehousing items while also discovering what is in our holdings, collecting metadata for photographs and writing descriptions for our audiovisual collection. All this work will go towards the materials continued use, access, and long term preservation goals.

At the center of La Historia’s work is the Mexican-American community of El Monte. Those who founded the site came from the barrios that had once existed in El Monte and understood the need for capturing the memory of the barrios before they were torn down to be turned into housing redevelopments. For La Historia, to establish itself was a challenge as they navigated the social-politics of the area and tried to create an autonomous space where their community could shape their own narrative. La historia is an archive of survival, constantly striving to have their voices heard and for their stories to not be erased. At every step of the way through events and new projects, they continue to find ways to keep the community alive and to have the community involved in their decision making process. I look forward to the rest of my journey with La Historia and how their work continues to develop with community in mind.

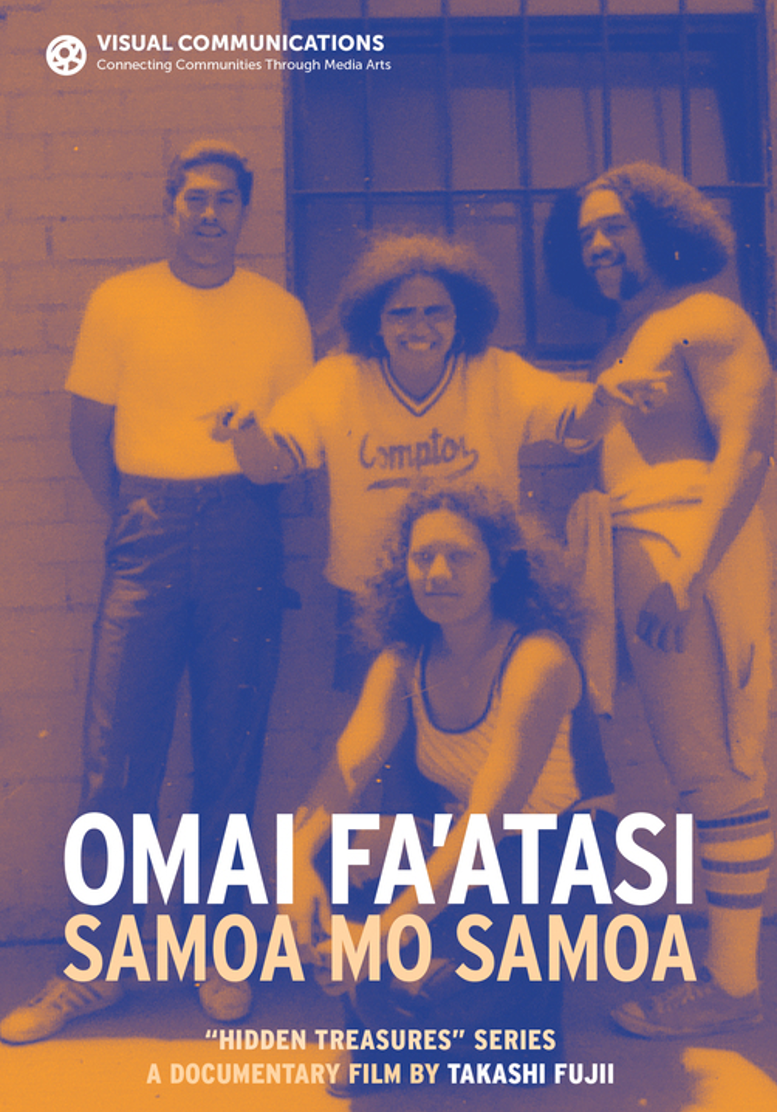

Archiving the Lineage of Pasifika Voices in Los Angeles

by Esperanza Bey || January 2024

Since October of 2023, I’ve had the pleasure of working as an archival intern at Visual Communications (VC), located in Little Tokyo. From my first interaction with the VC staff, it was clear that together we shared an interest in collecting and creating archives of Pasifika voices in Los Angeles. Founded in 1970, VC has served as a pioneer in the development of Asian American Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander media arts. In an effort to utilize media and art to empower AANHPI communities and build meaningful connections, VC hosts various annual programming rooted in record creation that are in constant dialogue with materials in their archival department. VC also upholds a conscious effort to ensure that those who are telling the stories of these communities are also within the AANHPI diaspora.

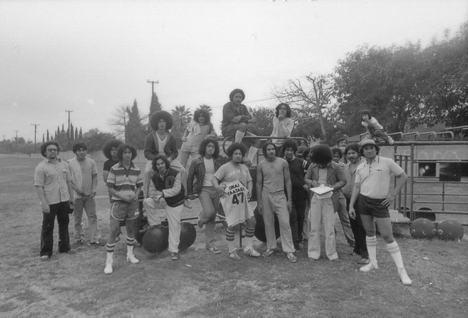

As a woman of Samoan descent and interested in developing a deeper understanding of the ontological practice of our elders known as Fa’a Samoa (the Samoan way), I was specifically in charge of archiving the Samoan collections at VC. With around 3000 items in their Samoan collection, my focus for this quarter was on digitizing the excess footage of a 1978 film titled Omai Fa’atasi: SAMOA MO SAMOA by Takashi Fuji. The documentary film focuses on a Samoan self-help organization based in Carson, CA during the 1970s.

With animated features by Ron Battle, the film demonstrates the remnants of colonialism in Samoan American households in the 1970s, assimilation, as well as the disconnect between Samoans raised in America and those raised in Samoa. Using an open-source video transcoder program called Handbrake, I digitized over 30 hours of footage stored in 65 DVDs to make readily available digital access copies.

In addition, I was able to curate several individualized digital archival material packages for VC’s Armed with a Camera (AWC) fellows. AWC is a fellowship program for emerging artists to engage with VCs archival collection and participate in record creation via media art. This year’s cohort is specifically focused on Pasifika artists and archival collections. My main responsibility was to review each of their goals for the project and determine which collections to pull material from to create a curated digital collection for each of them to access. Because some of their topics covered multiple ethnic backgrounds, their folders would range from materials from the Samoan American archival collections to materials on the Chamorro experience during the second World War.

So far, my experience at VC has been terrific. The organization has a great balance of being extremely organized and detail-oriented but also maintains a familial dynamic. Since my introduction to the VC space, VC staff has done a wonderful job at curating an experience that aligns with my passions as an archivist. I look forward to working more with the Pasifika collection, especially with inputting metadata for the digital collections, supporting the upcoming screenings of Omai Fa’atasi around Los Angeles, and helping to generate their upcoming cube installation with film grabs from Omai Fa’astasi. Overall, I am extremely excited for what the year holds for the rest of my internship and hope they will continue to center record creation and accessibility as their core values.

The Political Task of Stewardship in a Climate of Siege: How the Skid Row History Museum and Archive (SRHMA) Integrates Local Cultural Protocols into its Digital Workflows

by Azad Namazie || December 2023

My first encounter with the legacy and resistance embodied by General Jeff was at the Walk the Talk archival exhibition at the 14th Annual Festival for All Skid Row Artists. General Jeff, a figurehead not only for the steadfastness of Skid Row but also a luminary in West Coast hip hop, was a radical critic of the development interests, political maneuverings, non-profit “solutions,” and law enforcement agencies that have besieged and staked a claim to the 50-block Skid Row neighborhood. Amidst multiple wars being funded and armed by the US “on behalf” of other nations, General Jeff did not shy away from calling out a state maintained by permanent instability, displacement, and dispossession.

So, how do memory institutions, like the Skid Row History Museum & Archive (SRHMA), approach the political task of stewardship in this climate of siege? Specifically, how do they develop digital workflows that honor the local cultural character of the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD) and its records, SRHMA’s parent organization and the first performance arts group in the country primarily composed of unhoused folks?

For the past three months, I have explored methods of community art archiving and digital media preservation at SRHMA through cataloging and classification of digital assets documenting the annual Festival for All Skid Row Artists in PastPerfect CMS. I also manage inventory control, digitization, and digital preservation of the VHS collection, encompassing performances, community conversations, and even local television broadcasts. Through this work, and the hours nestled in the communal warmth of the upstairs museum mezzanine, I have been fortunate to bear witness to an emergent archival imagination through the lens of digital labor and sovereignty.

During the analog-to-digital conversion of cultural heritage materials that include raw, uncensored accounts of street life, welfare bureaucracies, criminalization, substance use, and even US imperialism, it is a political imperative to prioritize the protection of digitized materials from unauthorized access and resource extraction.

This is a fundamental component of digital archival processing in the current historical moment, as state-led displacement plans in downtown LA intentionally misrepresent the history behind the boundaries of Skid Row to further “develop” the area lawmakers are calling “Central City East.” In practice, protection of digital cultural heritage materials looks like robust data security measures, privacy protocols, access, and metadata workflows that are developed iteratively and collaboratively with records creators.

SRHMA archivists Henry Apodaca and Zach Rutland, both UCLA MLIS alumni, have also leveraged the agility of the digital technologies behind the PastPerfect CMS to integrate local cultural protocols into their collections information workflows. They have introduced new features within PastPerfect CMS, such as flexible name authority records, that recognize chosen names and anonymity. These customizations demonstrate how archivists can and should take bold actions to unearth contradictions in our digital applications and disrupt governance structures to uphold the sovereignty of records creators.

In my remaining internship period, I will formalize a digitization workflow and digital preservation plans for the VHS collection while Candy, my collaborator and fellow Mellon/UCLA Community Archives Lab intern, works on the MiniDV collection. Then, we will teach one another the formats, equipment, and software specifications of our respective projects. I am grateful for the opportunity to integrate teaching and learning into the media preservation workflow, a pedagogical approach that is often sacrificed for capitalistic productivity. I look forward to continuing to collaborate with Henry, Zach, Candy, John, Henriette, and LAPD records creators past and present, and all the troubleshooting, reformatting, revising, and reimagining that occurs between the folds.

Appreciating Collective Work In Community Archives: A Student Volunteer Project At S.P.A.R.C

by Andrea Domínguez || May 2023

For the past academic year, I have been working as an archival intern at Social and Public Art Resource Center (S.P.A.R.C). During my time at S.P.A.R.C I have worked on three major projects: I provided support with the acquisition of a collection, digitized hundreds of 35mm slides from the Mural Archive, and supervised 5 students from the UCLA Community Archives class. This last project was truly a rewarding experience, as it led me to appreciate how important and generative collective work can be in community-based archives (CBAs).

It is no secret that archival work can be solitary work, especially in ‘lone arranger’ settings, which are common in small archives, such as CBAs. And while I don’t have the space in this short blog post to unravel the practices that make it so, what I will say is that there is much to be gained if we work together, and if we value our collective work. I hope that by sharing my experience, both my peers and CBAs are encouraged to seek and create opportunities for this to continue to happen.

The preparation work I completed before working with students consisted in drafting a document that provided a brief summary of S.P.A.R.C’s archive and outlined the archival projects, alongside specific tasks and their objectives. I also created a slideshow as a visual supplement. Lastly, I led a field trip for ~10 students who had the opportunity to learn about S.P.A.R.C’s history, mission, and current projects.

After the field trip, 5 students signed up to complete 20 hours at S.P.A.R.C: Athena, Ian, Marissa, Marissa, and Senna. Together, we digitized 35mm slides from the International Mural Collection, completed archival processing tasks, and had a círculo discussion about CBAs. In our círculo, we wanted to bring together our creativity, invention, academic interests, and personal experiences to re-imagine archival processing in CBAs as an opportunity to network [1] and be in community.

What emerged from that círculo is a new approach we refer to as ‘intentional archival processing.’ In this approach, the focus shifts away from valuing productivity to valuing intentionality. It embraces moving slowly to include others in the process, and it proposes slowness as a methodology to create and nurture relations. Because being intentional is at the center, it allows and necessitates both individual and collective reflexivity. How we imagine intentional archival processing is by adding community activation moments that connect to archival processing tasks.

For example, before beginning the physical processing of a collection is a good moment to think about preservation. Granted, this is a broad topic that implies considering perhaps conditioning the physical space where the materials will be kept, housing, conservation needs etc. We propose this as a good opportunity to reach out to preservation/conservation experts to request a teach-in or workshop for the CBA processing archivist(s), archival intern(s), CBA staff, and to open it up to other CBAs in the region.

We also suggest surveying the materials with at least one other person. At its best, in the initial survey of a collection we can witness glimmers that illuminate the value and potential of the materials. These can make us feel excited, hopeful, and inspired. However, records can also be difficult, triggering, and even traumatic. In the best scenario, surveying with another person is a good opportunity to brainstorm ideas for community activation. In the more difficult scenario, offering and receiving accompaniment is a way to take care of ourselves and each other.

Our ‘intentional archival processing’ approach is not a complete methodology, and it is not meant to be prescriptive, but rather the opposite of that. Intentional archival processing will invariably look different in different CBAs, but at its core it should put into practice an ethics of care in archival work. To put it simply, the intentions are what care will/looks like for a specific community.

Lastly, I would like to add that I am thankful to S.P.A.R.C for hosting us, to Pilar Castillo for her trust in me to lead this student volunteer project, and to Dr. Michelle Caswell for designing a course that facilitates opportunities for students to gain hands-on experience in CBAs. And of course to my peers, I appreciate you, THANK YOU!

[1] Networking as a mycelial reference of interdependence and cooperation-based relationships, not corporate lingo.

Artists in Community at the Los Angeles Community Archive

By Daniela Reyes || April 2023

This year, the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA) celebrates ten years of collaborating with artists in building archival collections that enable its community to learn from each other’s art practices. Since 2016, LACA has made its home on the second floor of Chinatown’s Asian Center, where it shares office space among Chinatown Pharmacy and Hip Woo Hong, among others.

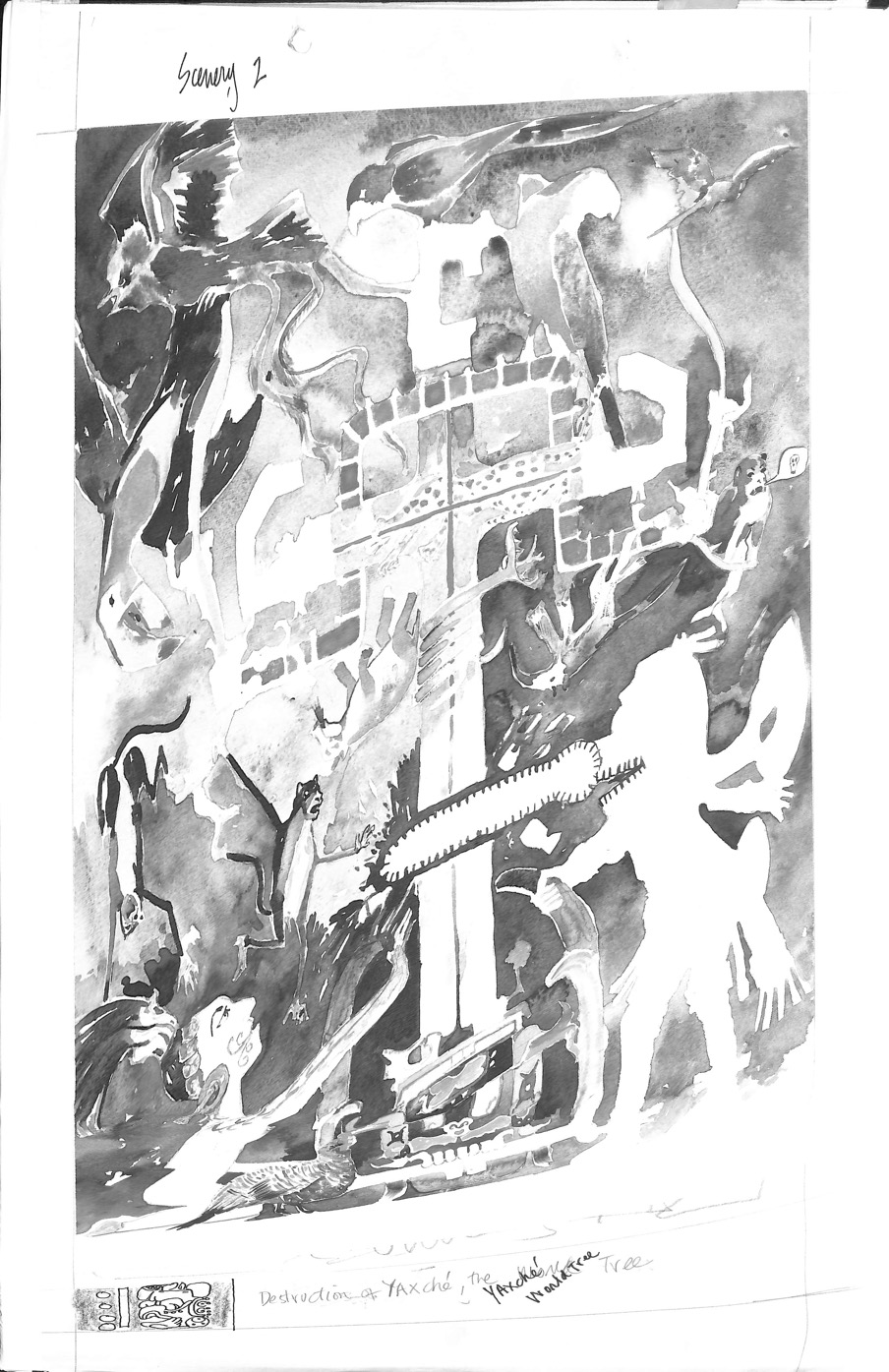

LACA serves as an archive and library dedicated to contemporary artmaking, as well as a space for programming such as exhibitions, performances, and workshops, to name a few examples. Through this internship opportunity, I have been fortunate enough to become acquainted with LACA’s collection of more than 33,000 items relating to contemporary art, which include art books, manuscripts, set pieces, performance apparel, and many other pieces of fascinating artist ephemera. One collection that I was able to process this past quarter was that of Ignacio Fernandez, a Cuban-born architect and artist who donated artist-books blueprints, manuscripts, and watercolor sketches to the archive. The collection was not only beautiful but thought-provoking due to the artist’s use of watercolor and the depiction of his family history.

Because LACA functions not only as a repository, but also as a space where programming happens, I have had the unique opportunity of witnessing how a community archive can use its physical space to build community in a variety of ways. Whether it is a fundraiser or a haunted house installation or, of course, an exhibit, LACA invites its users to not only conduct research using its materials, but to use the physical space for other types of learning or community building. This past February, LACA hosted Turkish born, LA-based artist Hande Sever’s exhibition To Thread Air, a multimedia project exploring the Cold War, the use of creativity as a tool for revisionism, and how art can aid statecraft.

To put it plainly, working at LACA has been fun. Meeting artists, working with their materials, and assisting with events aimed at community building has illuminated the kind of potential archives have if they are run by people who care not only about preservation, but about creating collections that reflect the lived experiences of their community. I feel lucky to have been gifted the opportunity to work with LACA’s team, who are compassionate, brilliant, and committed to their mission. Ten more years of LACA would be nothing short of a gift to artists, to Los Angeles, and to LACA’s community.

Digitizing the Many Voices of the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives

By Laura Dintzis || March 2023

The June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives is one of the largest archives in the world dedicated to collecting, protecting, preserving, and making accessible, lesbian and feminist history and culture. It was a grass roots archive started in Oakland in 1981 and originally called the West Coast Lesbian Collections. The archive was moved to Southern California in 1985 into the home of June Mazer and Bunny Mac Culloch, then into its current location on the second floor of the Werle Building in West Hollywood in 1989. The building sits between endlessly energetic bars, and the West Hollywood Library. It has remained a constant and endured many changes to the neighborhood over the years.

After rising to the second floor and moving through the door to the Mazer, you enter a space packed with archival boxes, books, posters, paper, and people working or chatting, bringing the space to life—despite the limitations that still persist during the COVID pandemic. Due to the sheer volume of materials in such a small space, care, collaboration, and urgency are fundamental to the archive’s daily function, especially when you consider there is even more knowledge held only within the people who make up the Mazer’s community. These are central values which have guided the work I’ve done alongside two other archivists, their teams, Mazer staff and volunteers, in order to continue the Mazer’s mission of providing multigenerational links between lesbians, queer people, and feminists, and to collect, preserve, and provide access to their history.

Within Mazer’s extensive archive, I have the opportunity to take an active part working with their oral history collections: digitizing cassette tapes from the Lillian Faderman Audio Cassette Collection, and managing born-digital oral histories taken by students in Dr. Marie Cartier’s Queer Studies course at California State University, Northridge. In addition to digitization and file management, I am working on creating a zine for the students, informing them about oral history preservation and best practices which hopefully can lessen the amount of file renaming and converting that the Mazer has to do when accessioning the projects. My other work involves the Mazer’s online presence, and includes creating newsletters, maintaining the website blog, as well as an ongoing effort to expand the video archive that is on the site.

I sometimes equate digital work with solitary work, but at the Mazer, that idea was immediately proved to be false. Not only did I get to work collaboratively to problem solve and research for these projects, but I had the opportunity to be part of the knowledge sharing that is essential at the Mazer. Completing these digital projects involves listening to and learning from the LGBTQ+ narrators that make up these collections; therefore, I’m never really alone when digitizing or checking files. It also involves listening to staff at the Mazer talk about their own relationship to these materials, and their own personal stories, letting us get to know each other along the way. These conversations are an essential part of preserving the collections, by noting personal context that can be lost or left out when project archivists, like myself, come into the process.

The work I am completing is done to help honor all of these points of information in an accessible and safe way, making them available to a wider audience now that they are in a digital form. At the Mazer, I get to explore methods for sharing digital archival resources securely, understand tiers of access, all while getting to reckon with alternative ways to represent materials online outside of a finding aid. These practices are things I’m passionate about in my MLIS program, and experiencing the reality of this work has been both challenging and rewarding.

Further collaborative work has come through physical processing. I recently started processing the Christy Amschler Collection, which is only one collection out of 293 other boxes that will be processed by the end of the year with two other archivists. The collection is mostly photos, sketchbooks, and 35mm slides, which have been wonderful to go through—allowing me to see the everyday joy of lesbian life, and to hear the stories of community care that brought the collection to Mazer. I am excited to continue my archival work and build relationships that will continue beyond this internship. I am grateful for this experience and the way it has shaped my own goals for future archival work.

Cataloging Chinatown History

By Eliana Urizar || February 2023

I am very grateful to have the opportunity of interning at the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC) as it has given me a well-rounded experience of the variety of work that one may encounter in a community-based archive. Aside from learning more about archival work, CHSSC has given me the means and the opportunity to explore more of the cultural and historical layers in Los Angeles. Here, I have had a chance to explore archive and digital collections, as well as a research library. I have witnessed the vitality of the research library, where research is conducted by all types of scholars looking into the Chinese American community in Los Angeles. This constant interaction between users and records has given me a good understanding of the scope of their work and the task at hand for archivists at CHSSC. Currently, the work at CHSSC involves the preservation of the histories of the five Los Angeles Chinatowns: Old Chinatown, New Chinatown, East Adams, City Market and China City.

CHSSC is in Chinatown, Los Angeles, giving them physical closeness to the community they serve. Their work is conducted in two houses and a storage holding area where physical archival collections are kept. One house accommodates their library collection, covering a vast range of Chinese American histories, including books on Chinese American last names and histories of Chinatowns across the United States. The other house is mainly used for digitization, cataloging, and other administrative work. Both houses, though, are places where the community makes archival decisions alongside the archivists and where research is conducted.

Thanks to the opportunity from the Andrew W. Mellon Grant to work with CSSHC this school year, I have been able to build interests and skill within community based archival work through my internship projects. My work functions have been to assist in recording the inventory of library materials as well as learning the ways in which CHSSC cares for their physical collections. However, it is in the cataloging of family photos that has been the most fulfilling part of my internship. The work of cataloging these photos has allowed me to work on an unexplored area of archiving. Through my work, I have found enjoyment and challenges in the process that have led me to want to explore this area more in the future. I plan to continue building my skills and knowledge so that I can simultaneously better contribute to this task while at CSSHC and for my own personal interests in cataloging.

Cataloging Visual Communication’s Past for an Accessible Future

By Chloe Reyes || January 2023

Founded in 1970, Visual Communication houses one of the largest archives dedicated to the Asian American experience in the United States. When I first walked into the space, I immediately felt welcomed by both the amazing staff and by the archive’s atmosphere. History lines the walls in almost a comforting way. Each week, I am so happy to participate in our Boba Runs, a ritual started by previous interns and staff as informal meetings to get to know one another. We relax with ice breakers and practice deep listening with each other. These practices not only create bonding experiences, but also mirror the values of Visual Communication, which advocates empathy, care and trust in its archival practice.

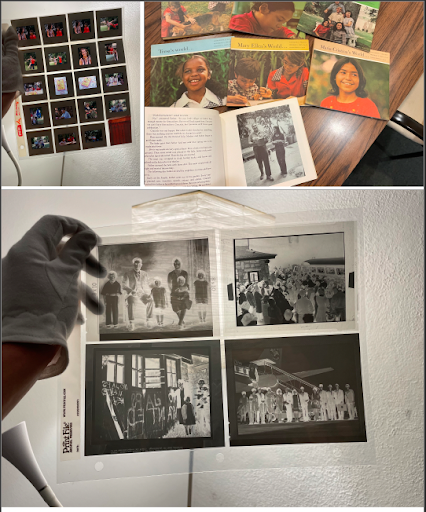

The vast VC Archive includes several bookcases and rolling racks which house original assets including negatives, color slides, 16mm film prints and moving image pieces stored on various magnetic media formats. In my internship, I have spent the majority of my time cataloging several photographic collections created by VC. One of these collections includes the Aardvark Publication Collections, a collection of approximately 6,000 images that observes the traditions, rituals and social conditions of Los Angeles’ vibrant Chicano neighborhoods. Commissioned by the LA Board of Education in the 1970s, and in collaboration with Visual Communications, these images were then turned into a series of educational booklets.

Another collection I helped to catalog is the George T. Ishizuka and Harukichi Nakamura Asian American Movement Collection, a nearly 40,000 black-and- white image collection documenting the events, historical milestones, and personalities created by VC’s founding members and core staff members in the 1970s and 1980s. By cataloging these collections, I have not only gotten hands-on skills with the cataloging process, but have learned more about the rich history of VC’s projects and staff. In addition to cataloging, I have also been digitizing physical assets, including 120mm negatives that document the Korean-American experience in the 1940s.

As the new year begins, the priorities for the archive are shifting to VC’s vast moving image archive. I’m excited to begin work on a digitization plan for the magnetic media, as well as helping to plan an infrastructure for easier online accessibility to VC’s important collections.

“We are all part of the same fabric”: Understanding and learning from the community in El Monte, California

by Bianca J. Sosa-Phal || December 2022

I became the Mellon Intern for La Historia Historical Society Museum (LHHSM) in September 2022. When I walked into the museum for the first time, it was empty; its white walls said nothing of what the building once held. Yet, I felt just as empty. I had little knowledge of the challenges, pains, and triumphs the Mexican American community in El Monte had experienced. However, as the collections began to make their way back into the museum, it became evident that my time at LHHSM would define my work and commitment as a future archivist.

In 1998, El Monte and South El Monte barrio members established LHHSM to effectively counteract the symbolic annihilation of Mexican American history in El Monte [1]. Their goal was to mainly document the experiences of those forced to live in segregated communities known as barrios. In addition, they believed that having a museum run by barrio members would remove the possibility of neglecting the voices and collections of barrio members and make the collections more accessible to the community. Finally, they hoped to make younger generations conscious of the existence of the barrios and informed them of how Mexican Americans had contributed to US history. LHHSM now stands as proof that El Monte Barrios once existed and thrived despite the harassment, discrimination, and segregation members experienced. LHHSM’s mission is to counteract the erasure, misrepresentation, and grotesque image of barrio residents, correct the Mexican American narrative, and strengthen the community of El Monte.

What is community? This word can be as empty as a building after a renovation or as profound and warm as your grandmother’s home—a home filled with objects, photographs, and stories that connect us and positions us in history. There is no better term to describe what transpires within the walls of LHHSM other than “community.” Community is key to the existence of LHHSM. The community nourishes the museum. The community informs our understanding of their history and provides the context of every photograph, document, and artifact. Contributing to LHHSM is a personal matter for community members because it is their story, narrative, and voice, and they get to tell it on their own terms [2]. LHHSM is not a historical building, nor is it located within the premises of a barrio; the building in itself is an empty vessel. What makes it significant, meaningful, and warm—like a grandmother’s home—is indisputably the many voices, contributions, people, stories, and collections that have made LHHSM their home.

During my short time at LHHSM, I have accomplished many tasks. For example, I conducted oral interviews and assessed, cataloged, and organized collections. In addition, I have participated in the progress of several grants, written proposals, and put best practices and protocols in place. However, this was only possible thanks to the participation of previous Mellon grant interns: archivists such as Lauren Molina, Samantha Abbot, Hannah Whelan, and Juliana Clark. They started the work I now get to finish. They have also set the example that I must continue my work, not hoping to finish but aiming to further it far enough for the next intern to carry it on.

My time at LHHSM and working alongside Rosa Pena (the president) have taught me more than what I can write on this page. All I can say is thank you for the opportunity, the stories, the tears, and the encouragement. My time here will pass, but the memories will never be forgotten.

[1] Michelle Caswell et al., “‘To Suddenly Discover Yourself’ Existing: Uncovering the Impact of Community Archives,” The American Archivist, 79, No.1, (2016): 57.

[2] Andrew Flinn et al., “Whose memories, whose archives? Independent community archives, autonomy, and mainstream,” Arch Sci, 9 (2009): 83.

Making SRHMA Collections Accessible in Service of Skid Row Placekeeping

by Emily Benoff || November 2022

Located two blocks from Main Street, the westernmost boundary of the 50-block Skid Row neighborhood, the Skid Row History Museum & Archive (SRHMA) is the only community archive with the mission of leveraging residents’ archival autonomy to document Skid Row’s activist, artistic, and recovery culture(s). Closely tied to the neighborhood’s history is the work of the Los Angeles Poverty Department (LAPD, but not that LAPD ), SRHMA’s parent organization and the first performance arts group in the country composed primarily of unhoused people. Amongst other narratives, SRHMA’s holdings chronicle LAPD’s 37-year (and counting!) effort to resist state-led displacement through participatory theater. As this year’s Mellon intern, I’m fortunate to collaborate with my predecessors—and current SRHMA archivists—Zachary Rutland and Henry Apodaca to amplify residents’ voices by facilitating the accessibility of the archive’s collections.

Working at SRHMA is especially meaningful because I get to witness the archive’s mission in action each time I enter the office. Zach, Henry, and I, along with myriad volunteers and visitors, work at a large table in the mezzanine. The communal nature of our workspace lends itself to mutual learning; whether I’m processing a collection, transcribing oral histories, or receiving hands-on training in analog media preservation, my work is always inspired by our collective imagining of inclusive archival approaches. Directly below us, LAPD holds its rehearsals. Us archivists engage with and are informed by the troupe members’ creative process. I’m honored to be building generative relationships with the co-creators of the records I am processing—those who are fighting for their neighborhood’s survival in the face of erasure and discrimination. This living archive encapsulates the very impulse that fueled my desire to become an archivist: the potential of archives to visualize how communities (re)negotiate and preserve their connections to place over time.

To surface Skid Row’s activist history, SRHMA has purchased a CMS with the intention of ingesting item-level metadata—now stored in GoogleSheets inventories—to be publicly browsable via the web. As part of my internship, I am leading a project to evaluate, normalize, augment, and prepare all legacy metadata to fulfill this long-term goal. This involves crosswalking metadata schemas; standardizing inventories; cleaning and enriching data values; and creating a local subject term thesaurus to aid cataloging and user searches. I am currently establishing a sustainable project workflow using the LAPD Photograph Collection as a case study, with scalability and adaptability in mind.

As an outsider to Skid Row, I rely on the ontologies of LAPD members (who are eager to share their stories) to accurately represent archival holdings. I center Skid Row residents’ information behaviors in all that I do, knowing that their activism secured their neighborhood’s borders and created SRO housing on Skid Row. As LA City Council is increasingly mobilizing public resources for the purposes of community displacement and downtown redevelopment, it is imperative that SRHMA make accessible and activate its collections in service of Skid Row placekeeping. I am excited to be contributing to this important work.

Activate the Archive Through Art: The Los Angeles Poverty Department’s Walk the Talk Parade

by Shawne West

Since September of 2021 I have been working with the Skid Row History Museum & Archive (SRHMA) as their Mellon Intern. Working and learning with two former Mellon Interns, Henry Apodaca (UCLA MLIS 19’-20’) and Zach Rutland (UCLA MLIS 20’-21’), I have been able to support the archive’s multi-layered focuses and commitments. Created by the performing arts organization, the Los Angeles Poverty Department (or the other LAPD), the archive captures the history of the LAPD itself – recorded performances, press, workshop and rehearsal materials – as well as the long and complex history of Skid Row itself.

LAPD’s entire history can be connected to the efforts to capture and honor the living moments of Skid Row’s history, through performance. A distillation of these efforts comes in the form of LAPD’s Walk The Talk (WTT) parade, a bi-yearly celebration of “people who live and work in Skid Row and who have made it a significant neighborhood and a place for solving the problems that other people have given up on.” Since 2012, through a community nomination process, LAPD has led this celebratory parade (brass band included) through the streets of Skid Row, stopping at locations representative of each honoree. Each stop features a short vignette developed by the LAPD performers, acting out the story of their journeys to Skid Row and their work on Skid Row.

This entire process, as well as the performances LAPD has done throughout the past 30+ years, encompasses the creative activation of archival records. The vignettes performed along the WTT route are distilled from 1-2 hour interviews with each honoree. These interviews are transcribed and then uploaded to the WTT Archive – a virtual repository that is publicly accessible, where users can learn Skid Row history directly from the individuals contributing to it. This is the work that a community archive exists to empower: communities who get spoken for in the traditional archival record reclaiming their narrative and speaking for themselves – and Skid Row is a community that often has decisions made for them, not with them.

My work as the SRHMA’s Mellon Intern in this project has been editing the computer generated transcripts – aiding in the creative distillation of an 1+ hour interview into a 15 minute group performance. The most recent WTT parade was Saturday, May 28th, and throughout the afternoon we danced and sang throughout the streets of Skid Row celebrating the 8 honorees – bringing the archive to life, with the community.

*************************************************************

The Importance of Documentation & Digitization in SPARC’s California Chicano Mural Archive

by Erin Schneider

This past year, I have had the pleasure of working with the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC). SPARC was founded in 1976 by Judith F. Baca, Donna Deitch, and Christina Schlesinger. Their mission is “to produce, preserve, and promote activist and socially relevant artwork; to devise and innovate excellent art pieces through participatory processes; and ultimately, to foster artistic collaborations that empower communities who face marginalization or discrimination.”

I have spent the majority of my time at SPARC in the Mural Archive, digitizing thousands of 35 mm slides from the California Chicano Mural Archive (CCMA). While the CCMA is only part of SPARC’s larger collection of thousands of mural slides, it is an extremely significant collection representing the importance of the Chicano art and social movement during the 1970s and on. The images range from the 1970s -1980s, and cover Southern and Northern California, from San Diego to Santa Rosa. Every image in the collection is unique, and full of historical significance. The murals depict everything from families and workers movements to local and international histories, from religious icons and cosmic ancient gods to so much more. Some of my favorite images include portraits of the artists themselves, or behind the scenes shots of murals in progress.

The immense importance of documenting these murals cannot be underestimated. While some of the murals represented in the collection still exist today, such as the Great Wall of Los Angeles by Judith F. Baca and collaborators (thanks to SPARC and restoration initiatives) or evolved with new murals (such as Chicano Park in San Diego) many have disappeared with time. Though SPARC has published an excellent book on the subject (Signs from the Heart: California Chicano Murals) using images from this particular body of work, the entire collection isn’t currently available for online research.

As we’ve learned, digitization does not necessarily mean access. Once the slides have been digitized, there are additional steps. Following the workflow established by my predecessors, UCLA students and interns Hannah Rogers and Michael Sokol, I have been digitizing slides into .tiffs, and creating .jpeg access copies, after adding metadata to each file including the artist(s), title of the mural, year of image taken, location, and dimensions. Eventually, the images and attached information will be uploaded to an Omeka site, for access and research purposes. This will create an exceptional repository not available anywhere else, and will provide crucial images illustrative of the Chicano mural movement. I’m honored to have contributed to this important process of documentation and digitization for the ultimate goal of sharing knowledge.

***********************************************************

Connecting to Everyday Lesbian History

by Hall Frost

When I expressed interest to my partner in applying for the internship at the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, she said “oh good, maybe you’ll learn something about our history.”

I scoffed and shot back “I know about our history!”

But the truth was, I didn’t actually know much about LGBTQ+ history at all. I don’t like drag shows or gay bars, I don’t like Pride, and the queer history I did know was all centered around trauma: Stonewall and Matthew Shephard and the AIDS crisis and a general historical ban on being queer in any way whatsoever. Couple that painful history with a culture that loves giving queer people the tragic, unhappy ending in popular media and the end result for me was to simply step away from it all.

Of course, the archives is filled with histories detailing these painful times; this collective trauma exists in some way in most queer people, even those like me who tried to avoid it all. But it’s also got baseball uniforms from the 1950s, cassettes filled with live music performances, thousands of periodicals that cover every topic from lesbian scuba diving to women’s health to sports and even books of poetry exclusively written by old lesbians; essentially, it’s got something for everyone. The Mazer is a place that offers community, connection, and joy.

The Director of Communications at the Mazer, Angela Brinskele, describes the Mazer as the “archives of the everyday lesbian.” It’s a place that offers an insight into lesbian life from the past, and thus offers many points of connection to meet a wide range of interests. During my time at the archives, we had researchers come in looking for everything from video footage of The Dinah Shore festival, to articles about lesbian separatism, and anything and everything we had related to women’s health clinics. For me, I ultimately found connection in the JoAnn Semones and Julie Barrow collection, which I spent the better part of six months cataloging at the item level.

This description project is being done to prepare the collection for future digitization, finding aid creation, and rehousing. The collection is made up of over 1500 photographs, spanning from the 1940s to the early 2000s. These photos tell the story of JoAnn and Julie’s lives.

My work with this collection involving describing each photograph in detail, compiling search terms, and documenting notes written on the backs of photographs, and it’s date and location. I poured over every photo, eventually coming to know the names of every family member, partner, even the pets! At times I felt as if I had known these two my entire life. As I worked, I finally found my connection to the community and lesbian history. First in a letter sent out in Christmas cards written by Julie Barrow’s mother in 1961 in which she describes Julie, 6 or 7 at the time, as “delighted at being a reader now, likes school but deserts the dolls for the great outdoors.” And again, in a group of photographs from the 1980s depicting JoAnn Semones and her friend pulling down wallpaper and repainting rooms, followed by well-earned beers at a card table set up in the garage in the home JoAnn just purchased.

Although I always hate to admit it, ultimately, my partner was right. I had a lot to learn about our history. Luckily, the Mazer is a special place that has a lot of amazing things in their tiny space and allows even those like me, who didn’t feel as though there was a place for me in lesbian history, to find their connections and community. I’m honored to have spent my time there and thrilled to know that the work I did will help other lesbians connect to their everyday history.

**************************************************

Leveraging Technology to Preserve California’s Chinese American Stories

by Anne Olivares

During the first quarter as the 2021–2022 intern with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California (CHSSC) located in DTLA’s Chinatown, I have been privileged to regularly work alongside two brilliant and enthusiastic individuals—Coryn Hardison, the site’s 2020–2021 Andrew W. Mellon UCLA Community Archives intern and current Collections Manager; and Linda Bentz, career archaeologist and long-term board member who oversees archives activities for the site. I am fortunate to have Coryn and Linda at my side as we discuss goals for the archives and the various challenges of community archives—storage space, digitization, and accessibility to the collection via various online platforms.

Since beginning with CHSSC in October, I have encountered members of Southern California’s Chinese American community in a variety of ways. The persistence of COVID-19 has complicated this, however I am grateful to say it has not completely hindered my ability to connect to the material CHSSC collects and maintains for their community, a challenge Coryn also dealt with in the previous school year. I have briefly encountered members of the community during on-site work at CHSSC, where board members drop in time-to-time and individuals occasionally drop off donations to the archives. I also had the privilege to volunteer at a Congressional Gold Medal ceremony for Chinese American veterans of World War II in Ventura in November 2021, including a living veteran in his 90s.

My goals with CHSSC have been a moving target that include many opportunities to handle physical material alongside an ongoing project of refining CHSSC’s online content and accessibility. For example, I have assisted with the organization of their extensive library—a collection of books related to the Chinese American experience as well as tangential histories—both physically and digitally via a Libib account created with the help of volunteers over the last several years.

Although I have a lifetime of experience working with technology, I have been challenged with digital exhibition creation using Omeka S, quite a steep learning curve I must admit, and assistance with the deployment of the archives’ first data logger. Before the end of this internship, I intend to gain experience with more technologies used by both small and large archives including: ArchivesSpace—to create finding aids for yet unprocessed material —and Airtable—to keep track of material related to the Southern California Oral History Project taken on by CHSSC members some years ago and the related metadata. CHSSC is also collaborating with Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West who utilize Airtable to gather and organize an incredible amount of data related to Old Chinatown for a future augmented reality project surrounding Los Angeles’ Union Station.

The experience with CHSSC will undoubtedly provide an incredible foundation for my future goal as an archivist and memory worker for small collections going forward. I have a passion for understanding and tackling the various challenges archives and collections outside of large institutions face, and this experience falls immediately within that realm.

************************************************************

Stories from El Monte

by Samantha Abbott

During my time at La Historia Historical Society Museum (LHHSM), I have had the pleasure of seeing how this archive and museum is closely tied to the community it serves. El Monte is located in the San Gabriel Valley, a few miles east of Los Angeles and LHHSM is situated near important community landmarks such as El Monte High School, the El Monte Library, and other museums, community centers, and parks.[1] LHHSM seeks to preserve the history of the city’s Latinx, Asian, and Native American communities over the past century through photos, artifacts, art, videos, and more. Joining LHHSM’s team for the past four months has granted me the opportunity to work directly with community members through oral history projects and raise funds for the archive through grants that support the archive’s preservation and exhibition work.

LHHSM acts as a point of connection where community members can link their lives to other El Monte residents across time. During a visit to the museum, one group of siblings browsed through the archive’s photo collection, which is displayed throughout the museum walls. These photos highlight daily life in the distinct barrios of El Monte and this family was able to recognize their father photographed throughout the museum and share his name with LHHSM. By identifying loved ones featured within the archive, community members share their knowledge and help to fill gaps in the museum. LHSSM’s guests are often both attendees and contributors, helping to name people within photos with limited descriptions, and are key parts of preserving El Monte’s history. Community members are also involved as part of the archive’s staff and board. LHHSM conducts its work through the dedication of its volunteer staff whose consistent advocacy has enabled its growth as a small community archive. With the support of programs and grants like the UCLA Community Archives Lab/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Internship Program, LHHSM has been able to expand its projects to accomplish its mission.

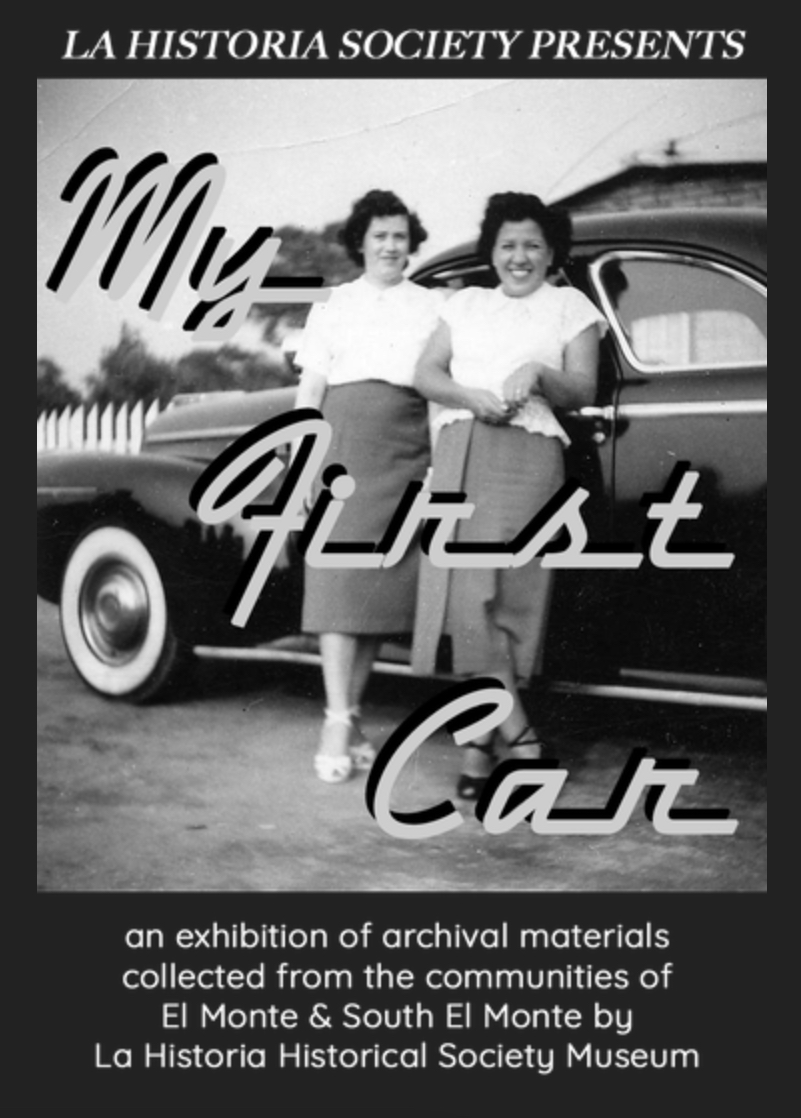

Community members further contribute to the museum through their participation as narrators in LHHSM’s oral history projects. My First Car, the museum’s most recent oral history project started by last year’s Mellon intern Juliana Clark, explores coming of age in El Monte and documents the relationships community members have with their first car and with the parts of El Monte they love to visit. Various interviewees have spoken of a car culture that connects family members and where oldies can often be heard playing through the speakers of cars riding through the city. LHHSM hopes to combine these narratives with photos and objects donated by the oral history narrators to illustrate their stories. It has been rewarding to speak with El Monte residents and as LHHSM expands, I hope to continue to support the archive’s team in bringing about exhibitions that represent El Monte’s close community to people across Southern California.

[1] City of El Monte. “About El Monte | El Monte, CA.” https://www.ci.el-monte.ca.us/334/About-El-Monte.

************************************************************

Visual Resistance: Exploring the Role of the Art Archive and Personal Archive-Building in Dismantling Carceral Narratives by Hannah Whelan

With the support of Andrew W. Mellon Foundation/UCLA Community Archives Lab, I’ve spent the past six months exploring methods of community art archiving and exhibition at Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA).

LACA is a community art archive and library that houses art-related objects and small edition artist’s books created by anyone who self-identifies as an artist. LACA is open to the public and is located in Chinatown’s Asian Center, where it has stood for the past five years.

The collection at LACA is artist-run, which means that living artists are donating, deciding what is valuable, and generating language for inventorying their work on their own terms. One part of this process that I particularly admire is that artists create the metadata for their donated materials, which is an exchange that both demystifies the metadata creation process and helps to narrow the chasm that can exist between archivist and donor perspectives on value and subject matter. LACA’s collection materials can be accessed through the LACA database, where born-digital materials are housed alongside pirate radio broadcasts, recordings of LACA programming, and scanned ephemera—all of which are archived at the item level.

Along with their digital and physical archives and library, LACA also maintains an exhibition space that hosts public events including panels with scholars and activists, book releases, performances, and temporary exhibitions. As I have spent time over the past six months becoming familiar with the LACA collection and working alongside those who care for it, I have also been developing an open call for an exhibition that I will be curating and exhibiting at LACA. The exhibition will feature works of art created on envelopes carrying correspondence between currently and formerly incarcerated artists and their loved ones on the outside.

Beyond adding decorative value, these works of envelope art, which are often collected and preserved in the homes of loved ones, offer community members experiencing incarceration a way to express their self-determined identities while maintaining crucial ties to their networks. By being deposited outside prison walls, these works allow senders and recipients to carve out space for communication and exchange to occur on their own terms—free from the physical presence of prison guards and the constant threat of institutionally-sanctioned destruction that exists when works of art remain in cells.

Because the stories that emerge from the circulation of envelope artwork hold incredible power and affective reach that resists state-generated narratives of dehumanization, these works are particularly vulnerable to surveillance, censorship, and destruction within carceral institutions. Given that my research at UCLA focuses on how archival projects intended to aid the incarcerated must avoid perpetuating surveillance and criminalization, the deed of gift I am creating for the collection takes into account the very specific vulnerabilities that exist with this project.

By collecting and exhibiting these works at LACA, we are using the space of the archive to resist carceral narratives and instead highlight projects of self-documentation and archive-building that convey the individual and collective humanity of those experiencing incarceration. The role that letter writing and envelope art play in disrupting carceral narratives and protecting the livelihoods of senders and recipients is one I have long been aware of, as my father has spent the past eighteen years in prison serving what will ultimately be a life sentence.

Through my research at UCLA and my work with LACA, I’ve found myself considering our correspondences as part of a history of artistic exchange and personal archive-building that is not only essential to the survival of our relationship, but will be indispensable to the preservation of his legacy as one that is not solely shaped by his incarceration.

While my connection to this show is deeply personal, I am inspired by any opportunity to explore collaboration between artists, archives, and abolition work. I am currently conducting outreach to currently and formerly incarcerated artists and am continuing to explore the various ways that artists and activists are using forms of visual expression and archive-building to resist carceral narratives. I look forward to continuing to develop the exhibit and associated public programming in conversation with those who have joined us as partners, and I am grateful to LACA for providing the platform to help activate these discussions.

*************************************************************

Digitization and Quality Control for Community Empowerment in the Visual Communications Archives

by Elizabeth Wood

In February 1942, two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which called for the “evacuation” of Japanese Americans from coastal areas. The order resulted in the upheaval of communities, forced people from their homes, and, in some cases, broke up families. Under the order, Japanese Americans (including children and the elderly) from all over California were forcefully imprisoned in desert camps and made to sleep in hastily converted horse stalls or crammed together in bare wooden barracks. Most people were imprisoned for three to four years, and while some returned to their homes upon release (homes that were often tagged with racist graffiti in their absence), many chose to relocate permanently. President Ronald Regan issued an order in 1988 apologizing for the internment camps, but California did not officially apologize until 2020.

Visual Communications (VC) is an Asian Pacific American community media arts organization located in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. Founded in 1970 with a dedication to documenting the civil rights and Asian American movements, their work has been preserved in the VC Archives, which have grown to include materials donated by Asian American families and individuals, including photo albums and scrapbooks. Among the collections are thousands of photographs (both from family collections and from efforts to collect and copy photos from the War Relocation Authority), newspaper clippings, and scrapbook pages documenting the period leading up to, including, and after the internment camps. Over the past several years, a concerted effort has been made by VC to have these documents digitized, and part of my work as an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation/UCLA Community Archives Lab intern at VC has been to cross-check the file directory of digitized images against binders of photographic negatives to ensure that every image in the photography collection has been digitized and cataloged.